A labor dispute is gripping Chicago’s troubled hotel landlords, whose pasts are incomplete but are now reaching deals with the city to house immigrants in two prime locations.

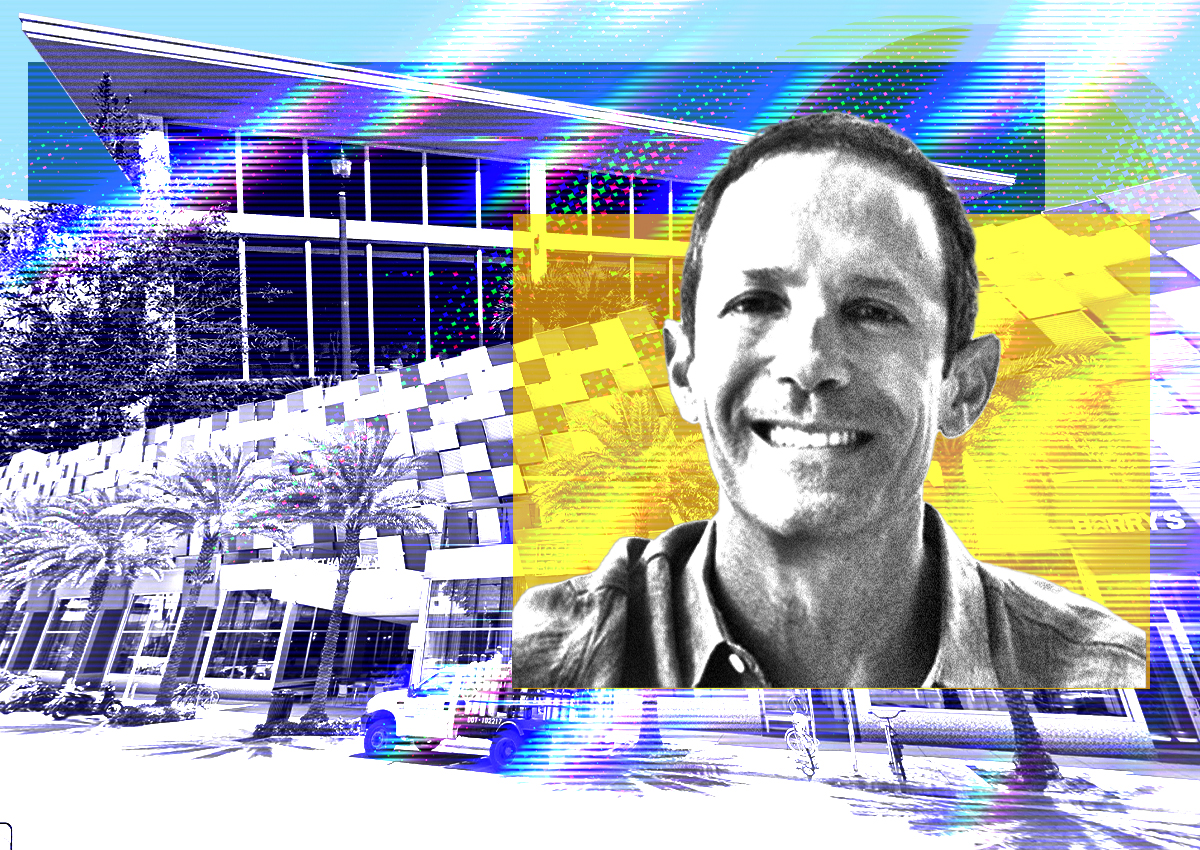

Remo Polselli is once again at the crossroads of dramatic government intervention and public funding linked to troubled real estate assets.

This time, though, it’s not about the millions in federal taxes the Michigan investor is allegedly dodging. Borselli found himself in this situation in the 2000s, when he served time in prison and was released in 2004 after pleading guilty to three tax charges. Separately, Porselli’s alleged underpayment of taxes was the subject of a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in May that rejected his contention that the way the IRS collects taxes tramples on his rights.

The Chicago hotel union was at the root of his next legal hurdle. Unite Here Local 1 claims its members were laid off during the pandemic at the Inn of Chicago, which is now part of Borselli’s portfolio, and now that the government has booked rooms to accommodate immigrants from the American South, Its members should therefore be allowed to return to work. Border personnel transported to Chicago from southern states.

Unite Here Local 1 is suing Polselli Enterprises, which purchased the 359-room, 22-story property at 162 East Ohio Street in 2021 for $13.5 million, a significant improvement over the $57 million loan it previously took on the property. Big discounts. Its former owner, San Francisco-based Chartres Lodging Group, defaulted on debt and the note was sold to New York-based Stabilis Capital Management in 2015. Stabilis has been trying to sell the property since foreclosure in 2017, and with the lodging market battered during the pandemic, Borselli is the recipient of it.

Borselli also bought the Standard Club building at 320 South Plymouth Court on the Loop for $9 million last year after residents of the 96-year-old building suffered membership declines before the pandemic and financial difficulties. He said he was approached by the city to use the properties to house migrants as southern state governments began sending large numbers of people to large northern cities.

While he has renovation plans for both properties — he has said he intends to rename the revived Standard Club as the Chicago Social Club, which will include two restaurants and 60 hotel suites — work on those projects remains on hold until the immigration crisis is resolved. Both hotels have been closed by their previous owners.

Chicago hotels had been closed since the early days of the outbreak until the city began housing immigrants there in May. The union alleges that Porselli did not recall former employees of the facility and ignored a city law passed to ensure that hotel workers laid off during the pandemic were prioritized to fill jobs when they reopened.

Still, Borselli said he had an agreement with a master tenant to run the property while it was serving as an immigrant shelter, a fundamentally different business than what hospitality workers are used to running.

“When the Chicago hotels reopen, union work will come back,” Borselli said in an interview.

The union and its lawyers did not respond to requests for comment. Mayor Brandon Johnson’s press office did not respond to inquiries about how much the city paid Porselli’s businesses to house the immigrants, whose properties were previously vacant and did not generate any revenue.

Standard club properties are free from labor disputes.

The city’s decisions about how to house immigrants recently sent to Chicago have proven tricky and contentious.

More than 10,500 asylum-seeking immigrants have arrived in Chicago since late August, straining the city’s asylum system as hundreds still sleep on police station floors, according to local news reports. The Chicago City Council approved $51 million in immigrant housing spending last month, though it’s unclear how much of that will go to the Chicago Inn and Standard Club, and the funding is only expected to last through June.

The deal to house the immigrants provides some income for Porcelli’s businesses that would otherwise be renovating, and probably pays little to no rent. The camera-averse 67-year-old entrepreneur said he is bullish on the recovery trajectory of Chicago’s hotel industry regardless, even though he said labor costs are higher here compared with other markets.

“Chicago is more expensive to operate than places like Florida,” Porselli said. “In Los Angeles, the hotel unions just went on strike for $25 an hour plus benefits. The unions do add costs, but the unions deserve credit for delivering really good, solid talent.”

He said he owned and operated 110 hotels in real estate over a 32-year period and has recently ventured into troubled properties, including a bid for the Hotel Felix in River North, The hotel was sold in foreclosure last year — the winning bid was a $29 million bid from Monarch Alternative.

“They still got a good deal,” Porselli said of the sale. “Chicago is trying to get out of the woods. Any hotel in Chicago is a good investment if you can hang on for the next two or three years. Our two properties—the Standard Club and the Hotel Chicago—are phenomenal buildings, and we Think they have a lot left.”